TODAY’S FIRST READING (2 Sm 7:1-5, 8b-12, 14a, 16)

FROM 2 Samuel 11b-12, 14a, 16:

“‘The LORD also reveals to you

that he will establish a house for you.

And when your time comes and you rest with your ancestors,

I will raise up your heir after you, sprung from your loins,

and I will make his Kingdom firm.

I will be a father to him,

and he shall be a son to me.

Your house and your Kingdom shall endure forever before me;

your throne shall stand firm forever.'”

From Ignatius Catholic Study Bible: Old and New Testament, page 474

The Davidic Covenant

The Davidic covenant is the latest and greatest of the Old Testament covenants. Following the steady buildup of covenants between God and his people over the centuries, beginning with Adam and continuing with Noah, Abraham, and Moses, the divine covenant with David brings the biblical story to a theological highpoint. Each of these ancient covenants helps to prepare the way for messianic times, but Jewish and Christian traditions agree that hopes for a coming Messiah are anchored most explicitly in the Lord’s covenant with David.

Nathan’s Oracle

The foundation of the Davidic covenant is Nathan’s oracle in 2 Sam 7.8-16, which responds to David intention to build a sanctuary for Yahweh. Nathan reveals that the king’s desire, although noble, is not part of God’s plan for his life. Instead, something more wonderful is envisioned. What David wants to do for the Lord hardly compares to what the Lord wants to do for David. This divine plan can be summarized under four headings.

1. Dynasty. Yahweh first pledges to build David a “house” (2 Sam 7:11). By this he means a dynasty, a hereditary line of royal successors, so that his kingdom and his throne will be “established for ever” (2 Sam 7:16). The house of David may have to be disciplined as times and circumstances demand, but the house of David will never be fully disowned like the house of Saul was when the Lord abandoned it on account of Saul’s failings (2 Sam 7:14-15). David’s dynasty will exercise an everlasting rule that is guaranteed by God.

2. Temple. Yahweh’s second pledge responds directly to David’s desire to build a Temple (2 Sam 7:2). The king wishes to begin construction on a worthy sanctuary, but, according to Nathan, the privilege a building a “house” for the Lord will fall to David’s royal “offspring” (2 Sam 7:12-13). This is an allusion to David’s son and successor, King Solomon, who pulls together a massive workforce to construct the Jerusalem Temple after his father’s death (1 Kings 6-8). The Temple thus serves as an architectural sign of the Davidic covenant.

3. Adoption. Yahweh’s third pledge is to create a father-son relationship between himself and David’s royal offspring (2 Sam 7:14). It is a promise that the kings of David’s line will be made sons of God by divine adoption. In this way, the covenant of kingship creates an especially close relationship between Yahweh and the anointed successors of David. It is implied in Ps 2:7 that the royal adoption of each king take place on the day of his coronation.

4. Law for Mankind. In response to the oracle, David senses that God, in pledging himself to these grandiose commitments, is initializing a plan to extend his blessings to the human race beyond Israel. What the Lord has revealed to him is nothing less than torat ha-adam, “the law of mankind” (see note on 2 Sam 7:19). The Law of Moses was a gift for Israel alone; but the covenant arrangement promised to David is a gift for Israel and other nations alike. This becomes visible in the days of Solomon, who recruits Gentiles from Phoenicia to assist with building the Temple (1 Kings 5:6, 18), who implores Yahweh to answer the prayers of the Gentiles who direct their pleas toward his Temple (1 Kings 8:41-43), and who instructs inquiring Gentiles from many nations in the fundamentals of godly “wisdom” (1 Kings 4:3- 10:1-10, 24).

Nathan’s oracle is worded as a divine promise, but its terms are guaranteed by divine oath. Whether a formal pledge is made on this occasion or afterward makes little difference. It is clear from other texts that Yahweh makes his commitments to David into a covenant (2 Sam 23:5; Sir 45:25; 47:11) by swearing an oath to David (Ps 89:3-4, 35-37; 132:11-12). And since God alone swears the oath, he alone assumes responsibility for its fulfillment. The Davidic covenant of kingship is an unconditional “grant”, meaning that Yahweh takes upon himself the unilateral obligation to make good on his pledges, regardless of whether or not David’s future line of successors proves worthy of this honor.

New Testament Fulfillment

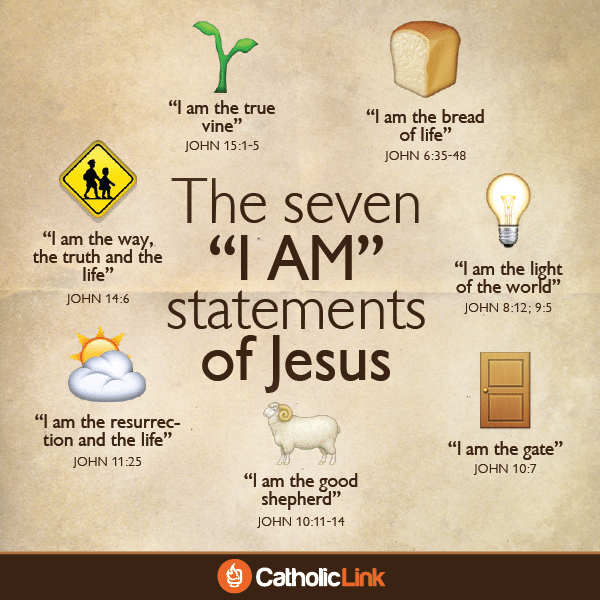

The pledges made to David are provisionally realized in Solomon during the golden age of the united monarchy and, to a lesser extent, in the centuries that the Davidic dynasty ruled in Jerusalem. But definitive fulfillment awaits the coming of Jesus Christ. He is the Messiah grafted into David’s dynastic line (Mt 1:1-16) and the one chosen by God to sit on David’s throne “for ever” (Lk 1:32-33). Like David, Jesus is anointed by the Spirit (1 Sam 16:13; Acts 10:38), and, like Solomon, he offers the wisdom of God to the world (1 Kings 10:1-10; Mt 12:42). The Temple he builds is not a stone-and-cedar sanctuary in Jerusalem but his body, the Church of living believers indwelt by the Spirit (Mt 16:18; Eph 2:19-22; 1 Pet 2:4-5). In the Resurrection, Jesus’ humanity attains the royal adoption promised to David’s offspring (Acts 13:33-3 Rom 1:3-4), and, at his Ascension, he commences his everlasting reign (Lk 1 :33) as David’s messianic Lord (Mk 12:35-37). Even now, he holds the key to the kingdom of David (Rev 3:7) and bears the distinction of being “King of Israel” (Jn 1 :49) as well as “he who rises to rule the Gentiles” (Rom 15:12). According to the very first Christian sermon, all of this is the fulfillment of Yahweh’s oath to David (Acts 2:29-35).

My take

There is a lot wrapped up in the Davidic covenant, as explicated in the excerpt above from the Ignatius Catholic Study Bible, is there not? It took about one thousand years for this solemn agreement to find its ultimate fulfillment in Jesus Christ. This is why we should pay particular attention to those incidents in the Gospels when Jesus is called Son of David. The persons saying this are not simply calling the Lord by any title — there is a whole depth of meaning behind it. Another word study, this time of “Son of David”:

The term is used eight times in the Old Testament, seven times referring to David’s biological son, Solomon, the other time to David’s son Jerimoth. For Solomon’s story (consider how he is a type [check out here and here] of Jesus — and how he’s not) see 1 Kgs 1-11 and 2 Chr 1-9.

The term is used sixteen times in the New Testament in eight different episodes or contexts, one of those being genealogies, one time referring to Joseph, Jesus’ foster father, one time used by Jesus in referring to David, and the other five times being addressed to Jesus. Note carefully (and use a good commentary), those contexts, especially the last five.

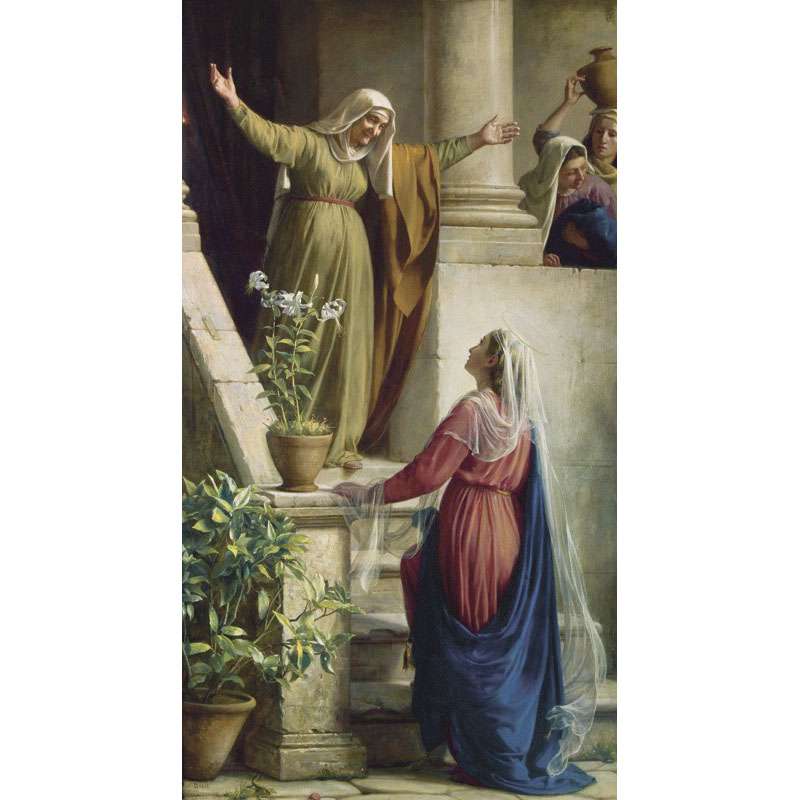

A last note, this on the Gospel reading (Lk 1:67-79). It seems to me that one major takeaway from Zechariah’s exuberant prayer is the value of silence. Zechariah had a lot of time to think, not knowing when — or if — he would ever get his voice back. Silent contemplation, without distraction, can yield great results. Let us take a lesson from this episode by spending much more time listening to the Lord and his mother (I imagine Zechariah heard Mary’s Magnificat and sat by while his wife Elizabeth and Mary were chatting in those three months leading up to the birth of his son) and much less time in idle conversation (yikes!). The results just might be amazing.

Blessed be the Lord, the God of Israel;

for he has come to his people and set them free.

He has raised up for us a mighty Savior,

born of the house of his servant David. (Lk 1:68-69)

AI generated — I could not find an image with all three figures that wasn’t licensable.

God bless!